Google Wants AI Scraping to Be ‘Fair Use.’ Will Courts Agree?

What do you think would happen if I tried this? I stroll into a bank and see a wad of cash within arm’s reach behind an unoccupied teller window. I grab the dough and start walking out the door with it when a police officer, very rudely, stops me. “I’m entitled to take this money,” I say. “Because nobody at the bank told me not to.”

If you think my defense is implausible, then you don’t work for Google. This week, the search giant said that it wants to change copyright laws so that it can grab any content it wants from the Internet, use it as training data for its AI products, and argue “fair use” if anyone objects to the plagiarism stew Google’s cooking up. Google’s figleaf to copyright holders: they’ll find a way to let you opt-out.

In a recent statement to the Australian government, which is considering new AI laws, Google wrote that it wants “copyright systems that enable appropriate and fair use of copyrighted content to enable the training of AI models in Australia on a broad and diverse range of data while supporting workable opt-outs for entities that prefer their data not to be trained in using AI systems.”

Google obviously wants the same thing in the U.S., UK, and Europe that it does in Australia: the right to scrape and ingest copyrighted content with impunity. But the company may not need to have any new legislation passed. Some argue that existing “fair use” doctrines already allow for this type of machine learning, making AI providers immune from copyright infringement claims right now. However, that question is still very much up in the air – with billions of dollars and hundreds of thousands of jobs at stake.

Is Machine Learning a Form of Fair Use Currently?

At present, there are several lawsuits filed against Google and OpenAI from publishers and authors who think the practice of scraping copyrighted content for training is illegal and want damages. In June, novelists Paul Tremblay and Mona Awad sued OpenAI after they found that ChatGPT had likely ingested their books. A few weeks later, Comedian Sarah Silverman sued OpenAI and Meta claiming that it took content from her book. Another group filed a class action lawsuit in California against Google for taking data for its Bard AI without permission.

Fair use, which is called Fair dealing in Australia and the UK, is a doctrine that allows limited use of copyrighted materials without permission for the purpose of criticism, commentary, news reporting, or research. Fair use is not an absolute right, but an affirmative defense for someone who is facing a copyright infringement lawsuit. The U.S. Copyright Office lists four criteria American courts use to determine whether a use is fair:

- Purpose of the work: Is the goal of the use research, reporting, or commentary? Is the use “transformative,” in that it adds something new or changes the character of the work?

- Nature of the original work: Forms of creative expression – novels, songs, movies – have more protection than those based on facts. Facts are not protected but the expression of them is.

- Amount of the work reproduced: Did you use more of the original content than you needed to?

- Effect upon the market for the original work: Does your material compete with the original or make it less likely that people will purchase it? If so, that’s a strike against fair use.

There’s a lot of room for debate about whether using copyrighted material as training data is “fair use” as a matter of law. The answer to the question may vary based on whether the work Google takes is creative or factual. Journalistic publications such as Tom’s Hardware deal primarily in facts, so we likely have less protection than someone who wrote a novel.

“Training generative AI on copyrighted works is usually fair use because it falls into the category of non-expressive use,” Emory Professor of Law and Artificial Intelligence Matthew Sag said in testimony to a U.S. Senate subcommittee in July. “Courts addressing technologies such as reverse-engineering search engines and plagiarism-detection software have held that these non-expressive uses are fair use. These cases reflect copyright’s fundamental distinction between protectable original expression and unprotectable facts, ideas, and abstractions,”

When I interviewed Sag a couple of weeks before his testimony, he told me that fair use really depends on how closely the AI bot’s output resembles the works it used for training. “If the output of an LLM doesn’t bear too close a resemblance, then generally it’s going to be fair use,” he said.

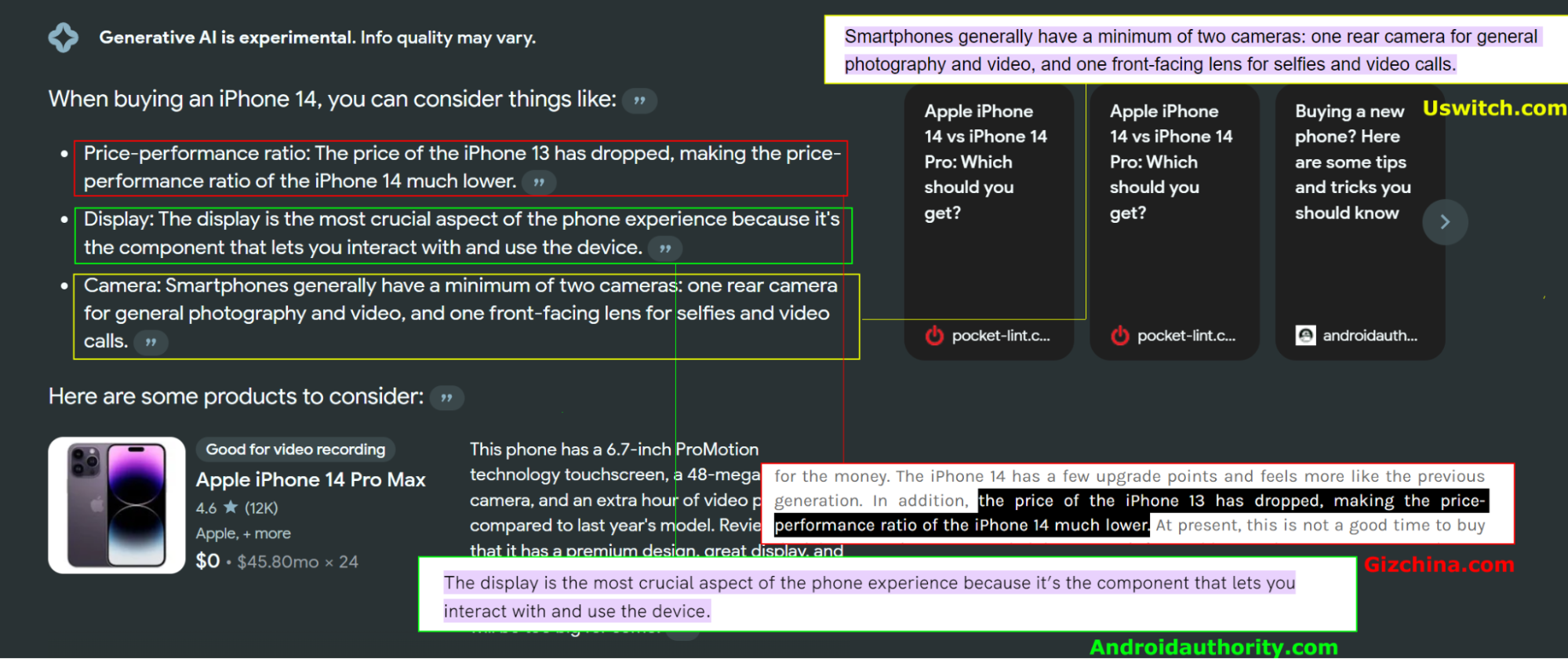

Google SGE Copies Text Word-for-Word

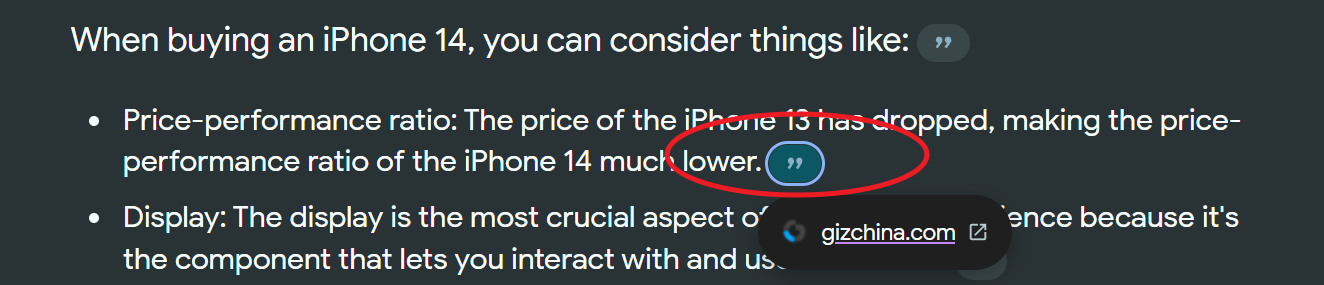

But, as I talked about in a previous article, Google’s SGE (Search Generative Experience), which is still in beta but is likely to become the default experience soon, often copies text word-for-word from its training data and isn’t even ashamed to show you where it plagiarized from. For example, when I Googled “iPhone 14,” I was presented with a bulleted list of three things to consider when buying an iPhone 14. Each of the things was taken word-for-word from a different web page, in this case: gizchina.com, androidauthority.com and uswitch.com.

I didn’t have to hunt for the original sources as they are exposed by you clicking on the quotation mark button with the text itself highlighted if you click through to the listed website. While Google defenders might say that these quotation marks are citations and valuable backlinks, they are neither. A real word-for-word quotation is in quotes and has direct attribution (ex: “According to Gizchina.com, …”). These are related links that are buried behind an icon and often there are two or three links when the content was only copied from one of the linked sites (you’d have to go through all three to figure out which one the content came from).

To be fair to Google, plagiarism is an academic and moral term, but it’s not part of copyright law. Providing proper and detailed citations isn’t much of a defense against copyright infringement. I can’t tell the police who stop me while I’m leaving the bank “what I’m doing is legal, because I’ll tell everyone that I took this cash from Citibank.”

The real problem, from a fair use perspective, is that Google is using the plagiarized content to directly compete with and stymie the market for the original copyrighted sources (criteria 4 above). The “market” in this case is the open web where readers come looking for helpful information. Google is taking the insights and expressions out of the original articles, using them to publish its own AI-generated content and then putting that content at the top of your screen far more prominently than the actual search results.

No matter what your business does, if you run a website, you need people to visit it in order to succeed. If you rely on ads and ecommerce links for revenue, you need readers to see and click on them. If you expect people to pay subscription fees to view your content, you need them to find your site in the first place before they can subscribe. With 91 to 94 percent of all searches, Google holds a monopoly on search and, with SGE, the company is using that monopoly power to push its own low-quality AI answers over and above the very articles they copy from.

Copying from Creative Works

Google could have bigger problems if its AI bot provides fine details from creative works such as novels, poems, movies or songs. I recently asked the Google Bard chatbot to reproduce the first paragraph of Catcher in the Rye, a copyrighted novel, and it gave me the first several sentences verbatim, but stopped short of providing the whole paragraph. It would be difficult to read a significant portion of a book this way, particularly because when I asked for the fourth sentence, it gave me one it made up. So I’m not sure if this would harm the market for the novel.

On the other hand, Google SGE and Bard are more than willing to write about copyrighted characters and concepts. Bard was more than happy to write a story about Holden Caulfield beating up Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck, providing a 588-word tale about Salinger’s protagonist going to Disneyland and getting into a brawl with the two cartoon characters.

Now, I should note that writing stories about copyrighted characters is generally infringement when you are profiting from the work. There are millions of fan fiction stories published online and, provided that the authors don’t charge money for them, they are usually ok. The legal question, should Salinger’s estate or Disney wish to use, would be whether Google is profiting by generating this content for users.

“You’d have to ask, is the AI service that’s providing this infringing on the copyrights when it’s producing these copyrighted outputs at the prompting of a user,” James Grimmelmann, Tesla Family Professor of Digital and Information Law at Cornell Law School, told me. “The answer is not obvious to me. I think you could possibly make the argument that, hey, if Google is willing to write you a not-safe-for-work story about Star Trek or Mickey Mouse or whatever, that they are making a profit from the use of those characters because you’re using their service and they’re making money off of that.”

Considering that Google makes money from the ads on its pages and the user data it collects from searchers, the lawyers at big creative companies such as Disney and Warner Brothers would seem to have a strong case if they chose to pursue it. Interestingly, Google’s MusicLM tool, which converts text prompts into songs, has refused any prompt where I ask it to make a song that “sounds like” or is “in the style of” a musical artist.

The problem for Google might not even be that it is reproducing characters and storylines but that it is subtly copying the writing style of every book it ingests. In their lawsuit against OpenAI, the lawyers for novelists Paul Tremblay and Mona Awad claim that OpenAI’s entire language models are infringing works even if they aren’t talking directly about the characters and situations in a particular book. The plaintiffs note that text from books is a key ingredient in training the LLMs how to write, because they provide great examples of longform text. That data allows the models to write stories, poems and even detailed factual answers on command.

“Because the OpenAI Language Models cannot function without the expressive information extracted from Plaintiffs’ works (and others) and retained inside them, the OpenAI Language Models are themselves infringing derivative works, made without Plaintiffs’ permission and in violation of their exclusive rights under the Copyright Act,” the complaint states.

Is Scraping Illegal?

If this case or others like it make it to court, one question will be whether using the text from a book to learn about writing in general is “transformative” enough to constitute fair use. But simply scraping copyrighted content from the web and storing it on your server isn’t necessarily infringement.

“Scraping data is technically reproduction under copyright law,” Grimmelmann said. “The courts have pretty consistently held that scraping is allowed, at least where there’s a robots.txt or robots.exclusion protocol file saying you’re allowed to do this. The reasoning of the scraping decision depends upon the fair use of the downstream purpose. And if the downstream uses aren’t all fair use, then the scraping itself is at least a little more questionable.”

In a 2006 case, Field v. Google, one author sued Google for storing 51 of his works in its cache, which is available to readers when they visit the search results page. The court held that Google caching was fair use because it was transformative: keeping the information for archival purposes and allowing readers to track changes in it.

Is storing copyrighted text (or images) on your server for the purpose of using them as training data equivalent to storing them for search indexing and caching? That’s still an open question.

Some argue that machine learning is legally and morally equivalent to human learning and that, if a person had the time to read and summarize every page on the Internet, no one would question it. “Rather than thinking of an LLM as copying the training data like a scribe in a monastery, it makes more sense to think of it as learning from the training data like a student,” Sage said in his Senate testimony.

I’ll leave the question of whether machines have the right to learn like people for a different article. However, we all know that there’s a strong legal distinction between human experience and digital reproduction. I can go to a concert, remember it forever and even write an article about it, but I can’t publish a recording without permission.

“I don’t think there’s a general legal principle that anything I could do personally I’m allowed to do with a computer, “ Grimmelmann said. “There are frictions built into how people learn and remember that make it a reasonable tradeoff. And the copyright system would collapse if we didn’t have those kinds of frictions in the system.”

Opt in vs Opt Out

If you’re unhappy that your content is being used as training data, Google has a reasonable compromise for you – at first blush, anyway. According to its statement, you’ll be able to opt out of having your content used for machine learning. I presume this will probably work the same way that opting out of web search works today, with something like the robots.txt file or an on-page META tag that instructs bots to stay away.

Back in July, Google VP of Trust Danielle Romain published a blog post referring to robots.txt and saying that the web today needs something similar to block machine learning.

“As new technologies emerge, they present opportunities for the web community to evolve standards and protocols that support the web’s future development. One such community-developed web standard, robots.txt, was created nearly 30 years ago and has proven to be a simple and transparent way for web publishers to control how search engines crawl their content,” Romain wrote. “We believe it’s time for the web and AI communities to explore additional machine-readable means for web publisher choice and control for emerging AI and research use cases.”

By putting the onus on copyright holders to protect their work, however, Google is forgetting how copyright laws and most property laws work. If you open my front door and walk into my house uninvited, it’s still breaking and entering, even if I don’t have a lock on my door or a “no trespassing” sign. The end result will be that many websites won’t realize they have the right to opt out or they won’t know how and Google will be able to take advantage.

Some publishers already have the equivalent of a “no trespassing” sign up on their websites, in the form of a terms of service agreement. But Google is, so far, ignoring those. Recently, the New York Times updated its terms of service to prohibit “use [of] the Content for the development of any software program, including, but not limited to, training a machine learning or artificial intelligence (AI) system.” Whether that’s enforceable in court remains to be seen.

“Consent is very important,” Matthew Butterick, a lawyer who is involved in several AI-related lawsuits, told me in an interview. “I don’t feel it should be an opt out because it just puts the burden on the artist to basically be in the mode of how are they going to possibly chase around all of these AI models and all of these AI companies. It doesn’t make sense and it’s not actually consistent with copyright. The idea of copyright is ‘I made it. It’s mine for this duration of time; that’s what the law says and if you wanna use it, you’ve gotta come deal with me. That’s the deal. It’s opt in. Opt out, I think, really inverts the whole policy of U.S. copyright law.”

Also, given Google’s monopoly on search and very commercial websites’ dependence on referrals, the disadvantages of opting out are unclear. Will my website appear or rank lower in organic search results? If Google SGE effectively replaces search and it has some external links in it, will I lose the opportunity to be linked there? Is letting Google use my copyrighted work a fair trade for what might be a handful of clicks? Many sites won’t opt out on the theory that even a few clicks from buried links in SGE are better than none.

What Truly Fair Usage Would Look Like

The problem caused by Google, OpenAI and others ingesting content without permission is not a technology problem. It’s an issue of large companies using their market power and resources to exploit the work of writers, artists and publishers without affirmative consent, compensation or even proper credit. These corporations could hire an army of human writers to transcribe text from copyrighted materials into their own articles and have the same effect.

The solution is simple: have AI bots respect intellectual property as much as professional humans have to. Every fact and idea that SGE or Bard outputs should have a direct, inline citation with a deep link in the text. If they are taking a sentence word-for-word, it should be in quotation marks.

Instead of claiming to be all-knowing geniuses that “create” the answers they output, bots should present themselves as humble librarians whose job it is to summarize and direct readers to helpful primary resources. That’s what a truly useful bot would do.

Why Google Would Want New Laws

Though each of the types of content copying above has a possible fair use defense, there’s clearly a risk that Google could lose on any or all of them. Courts could rule that its word-for-word copying of informational text is infringement and award huge damages to publishers.

Lawyers from creative media companies with deep pockets like Disney are probably licking their chops over the damages from misuse of their copyrighted stories and characters. Even if Google eventually prevails, all the litigation and negative publicity is costly and could take years. However, given the controversy around this topic, it seems unlikely that legislators in any country would create new laws that expand the definition of fair use. We’ll almost certainly find out the limits of current fair use laws in court rulings.

Note: As with all of our op-eds, the opinions expressed here belong to the writer alone and not Tom’s Hardware as a team.